“Leave a Light On for Me” – Day of the Dead and its Transformation to America

In the first days of November, after stuffing oneself with Halloween candy and being haunted by last night’s horror movies, another colorful holiday comes around the corner. However, instead of spooky legends or trick-or-treating, it’s the heart-warming reunion of the living and the spirit realm, that is the Day of the Dead.

The Day of the Dead – or Día de (los) Muertos in Spanish – is a holiday celebrated from Nov. 1 to Nov. 2 in which families and friends welcome back the souls of their deceased loved ones with food, stories, and all-around celebration. Though it is strongly identified in Mexico, this holiday has spread throughout other Latin American countries and even the United States, thanks to its ever-growing Latino population.

El Día de (los) Muertos is a blend of the ancient Aztec celebration of the Lady of the Dead and Queen of the Mictlān (the underworld), Mictēcacihuātl, and Catholicism brought by the Spanish with holidays such as “All Saints Day” & “All Souls Day” to what has become the holiday we know today. In the modern day, people wear skull masks and face paint, family and friends spend time at the gravesites of their loved ones, and, most famously, set up altars – or ofrendas – to personally showcase these souls.

Elmhurst University is no stranger to the holiday as there are many events students are encouraged to take part in, regardless of cultural background. Since 2013, EU’s Alpha Mu Gamma displayed an ofrenda in Founder’s Lounge and the A.C Buehler Library, decorating it with flowers, candles, decorated skulls, papel picado banners, food, photos, and personal belongings of what these souls may have liked when they were alive. They have also invited elementary school students from Bensenville Public School District 202 to come in and learn about Día de Muertos, sharing many of its traditions.

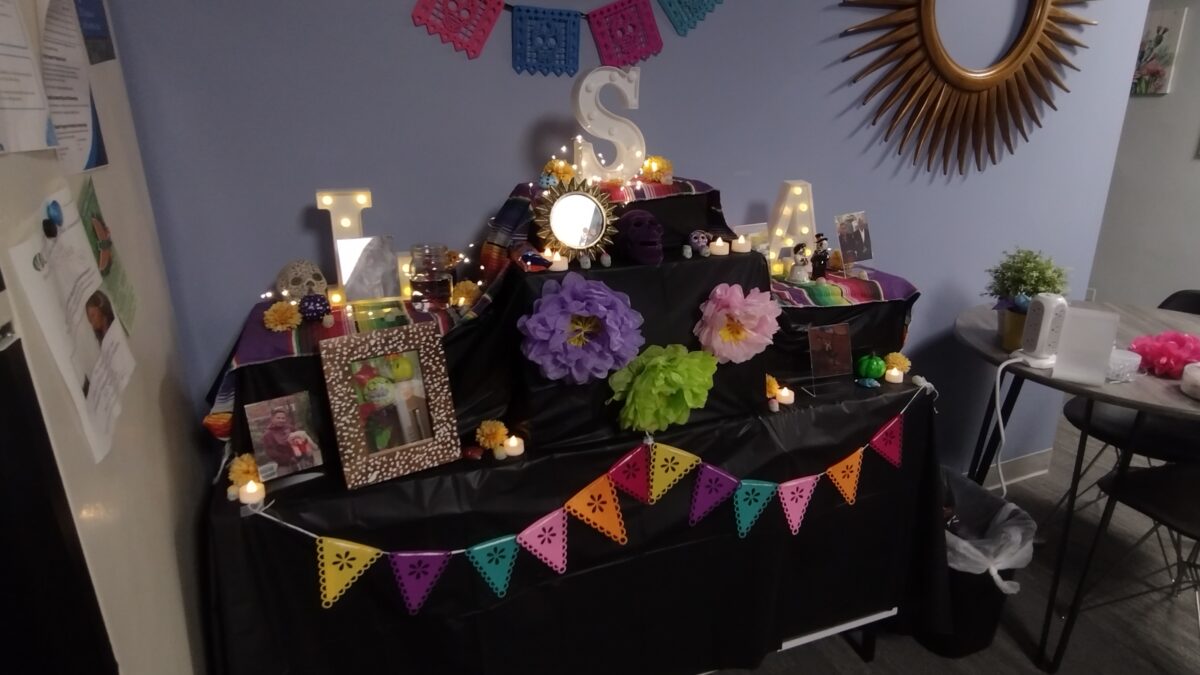

EU’s Latino Student Association also made an ofrenda in El Centro de la Promesa Azul, dedicating an event on Oct. 31 filled with snacks, calming music, and sharing stories of loved ones with acquaintances. They encouraged people to bring in photos of their family members up to Nov. 2.

There is much more than simply lighting up candles and making sugar skulls, it’s about sharing stories of the souls and remembering who they were.

Jennifer Paliatka, EU’s librarian and associate professor, helped provide open spaces in the library for the ofrendas Alpha Mu Gamma set up currently for over 10 years. Despite not being of Mexican heritage, she states for The Leader, that she contributed a photo of her loved one for the ofrenda in Founder’s Lounge: her mother, Clare Paliatka.

“My mom passed away in April. She was a pretty amazing lady,” Paliatka said. “She went to college and graduate school at a time when not too many women were looking for careers. In 1964, she became a licensed social worker and worked in the field of adoption. She raised four children, and when we were grown, she tutored adult immigrants who were learning English. She instilled a deep love of learning in me. If it wasn’t for her, I may not have adopted my daughter.”

Paliatka stated that though her family doesn’t celebrate the holiday, they did grow up in Catholic tradition and attended Mass on “All Souls Day” and “All Saints Day.” Having been exposed to the holiday by living in the Chicagoland area, she attempts to adopt the holiday to be closer to her mother. As simple as wearing her mother’s favorite color, hot pink, as a scarf or a pair of earrings, so she could remember her mother fondly.

“Instead of grieving the loss of her, I am trying to celebrate her life, her beauty, her spirit, and all those parts of her that continue to live inside of me,” Paliatka states.

The EU faculty weren’t the only ones contributing to the ofrendas. John Tolle, an EU student in the graduating class of 2026, sent in a photo of his father, Larry “Pete” Tolle.

“My dad was an intelligent but undereducated, quiet, nice guy from the heart of Nebraska, and he grew up in a town called Grand Island. He was in the U.S. Navy (he lied about his age to get in a year early) and worked in a machine shop for over 40 years in Rockford, IL,” Tolle recalls. “After I turned 5 years old, I only knew him on the weekends. His life was humble and simple, and he loved his grandchildren without hesitation. He died after a terrible battle with lung cancer after a lifetime of smoking; he started when he was only 11 years old! I will miss him and the quiet positivity he brought to our family. I will miss his frustration at the game of golf and his exuberance when he got the ball in the hole from a lucky chip or put. He also taught me to swear like a sailor.”

Like Paliatka, his Catholic family didn’t have any Hispanic heritage nor did they attend religious ceremonies. Though his family didn’t practice the holiday and he simply happened to stumble across it, he states that he has, “personally always loved the tradition of honoring the dead in such a cheerful and beautiful way.”

“Honestly, talking to family about our lost loved ones is always a warm reminder of how much we miss them and how much the world was better with them in it,” Tolle states in an email to The Leader. “I know that sounds counterintuitive, but it makes us both happy and sad at the same time.”

Another student of the same graduating class, Alejandra Galvan, contributed multiple photos of her grandparents, Abuelito Flavino, Grandma Diane, and Grandpa Ermanno, to the ofrenda due to her Mexican heritage.

“My abuelito Flavino was my mom’s father. He was quiet, kind, and stuck to his work. He worked with glass and would make mirrors. He taught me how to cut glass using an exacto knife in his little corner shop in Mexico. He was one of the first people that treated me like an adult and trusted me to be on my own. I remember being jealous that he had chickens and puppies in his courtyard, and he would always respond by letting me play with them,” Galvan explains. “I didn’t ever meet my Grandpa Ermanno, but I did know my Grandma Diane. She was my step-dad’s mom and her energy was infectious. She would never let you see her without her wig and makeup. I aspire to have that dedication in the future. I remember when I was younger I would go into her room after class, jump on the bed, and ask to listen to the police radio with her. She loved that app, and it was running almost all day. If it wasn’t the radio app it would be bingo. My brother and I learned to love bingo because of her, and we always reflect on it fondly. The world was a good place with them in it!”

Galvan shares with The Leader that while she grew up learning about the Day of the Dead through her family, she wasn’t able to have the whole experience.

“We never had an altar, but we would put their picture up and place it next to a drink or a light snack. My grandma in Mexico would always make a large ofrenda with colorful decorations and foods. I regret not doing it at home, because it is such an impactful celebration of memories,” Galvan expresses. “I would love to go to Mexico to see my relatives’ altars, because I know how much effort they put into it.”

Being Mexican-American myself, I share a lot of the same sentiments, as many in the Latino community do, in wanting to be connected with family and our cultural roots. Thanks to EU hosting the ofrendas on campus, not only did it bring the connection we wished for, but it also helped bring light to our culture to new eyes and generations.

“I was so excited that [Alpha Mu Gamma] was doing [the ofrendas], because it allowed me to find a place for my grandparents, but also to immerse myself into my culture,” Galvan said. “When I showed my mom that I had put my grandparents on the ofrenda, she immediately told my family and shared the experience with them. It is a lovely way to stay connected with your family because you all unite to remember someone you have lost.”

Representation of the Day of the Dead and Latino culture has also made its way into animated movies such as Disney’s “Coco” and Gutierrez’ “The Book of Life,” in which the Latino community feels seen through incredible storytelling and art.

Galvan recalls, “I remember watching “Coco” in Spanish with my mom and we both ended up sobbing by the end of it. Both movies tell a beautiful story of my culture and it teaches kids that there are these wonderful cultural practices around the world that we can learn about.”

When immigrant families have to adapt to the U.S., it isn’t uncommon for them to try to be “more American” by learning English and engaging in pop culture. Even so, some families believe that it’s incredibly crucial to keep traditions, such as Day of the Dead, as part of their culture.

“I think it allows for community building, and it connects us all together with a common purpose. I’ve heard stories of late relatives visiting my family’s ofrendas, taking bits of food off of the plates, and even how the energy feels different and happier on those days. Regardless of what you believe, Day of the Dead is meant to offer comfort for both the living and the dead,” Galvan states.

Regardless of cultural background, the Day of the Dead brings up the discussion of death and what it means for each individual. For some, like Galvan and Tolle, death is simply a part of life. Paliatka also shares that interpretation but brings in a different perspective, one of age.

Paliatka explains, “I think not only are there cultural differences in people’s perception of death but also generational differences. I used to be so terrified of death when I was younger. But now I am in the middle part of life and I have buried both my parents in the past two years. For them, death came with suffering. So, now that I am older I saw it as a blessing when they both passed away. Their souls and their bodies were finally at rest.”

People hold many stories of their childhood. Memories of their loved ones. In the spirit of the holiday, I interviewed my mother, Maria, about her father and my grandfather, Manuél Rubio Avila. She’s a legal immigrant who came from Mexico to Chicago, and hasn’t been able to see her family for over 20 years.

I was told many stories of Papa Manuél. He was an incredibly intelligent man and a human calculator, despite only finishing primary education – or America’s equivalent of the 6th grade. A hard worker who valued punctuality and honesty, which earned the respect and trust of his fellow acquaintances. In Mexico back then, citizens had to do mandatory military service in a lottery-like system; if you got picked out of chance, you had to do it. My grandfather was chosen and served for a couple of years. As a reward, the government gave him a hunting permit, and in turn, he became an incredible huntsman and sharpshooter out of his friends. He hunted down wild animals like rabbits and hogs, never missing a single shot, within the permitted grounds. He was a skilled craftsman, being able to become an expert of something just by observation. He used broken pieces of pot and made a beautiful patio fountain with a working water system. In the town’s church where my mom usually went, there is a sacred room dedicated to the Virgin Mary of Guadalupe in which people came in and placed gold rings on the fingers of the statuette as offerings. However, due to how accessible the room was, there were a lot of cases of the rings getting stolen overnight. As brilliant as he was, my grandfather constructed a door with a complex mechanism that was attached to the frame, which he was the only one who knew how to open. He was also kind and fair as a husband and father, who loved his family with all his heart. Papa Manuél, unfortunately, passed away due to pancreatic cancer at the age of 50. My mother was around my age when it happened, and his passing was what pushed her to come to the U.S..

When I asked her about the changes in celebrating the holiday in America, she emphasized that, “It’s different, obviously because my family isn’t here so I can’t simply sit with them and tell stories, or just spend time with them. Not being able to do it within the same moment as they do. Especially when it comes to my dad. And one of the other things is that what I would usually put things on my dad’s ofrenda, I can’t exactly find them here. Even if the things I find are simple and cheap, as long as I have his flowers and photo, remembering who he is with you all, and who he means to me is what matters. I want to remember who he is because I want him to continue living in the spirit realm, to not cease to exist and forget about him.”

She faced much discrimination living here in the U.S. but was never ashamed of her culture and its traditions, and wished for my siblings and I to do the same.

“It’s important to keep holding on to these traditions because at the end of the day, your heart is separated in two parts. It’s a bit difficult because one half will always yearn for home, in my case it’ll be Mexico, and then you have the other half that is reserved for the country your children were born in. The heart of an immigrant will always be split, especially when you have learned to adapt to a foreign country. For that heart not to be broken completely, you try to bring all of your traditions, language, food, and the other things we enjoy and remember them in a way here. Perhaps it isn’t a hundred percent exactly how we do things, but with the small things I can teach my children, I want them to conserve the split in their hearts. One for the land of their parents, and the other for their own country, both sides just as beautiful as having a whole heart.”