The Chapel Incident: a look at racial tensions in Elmhurst College history

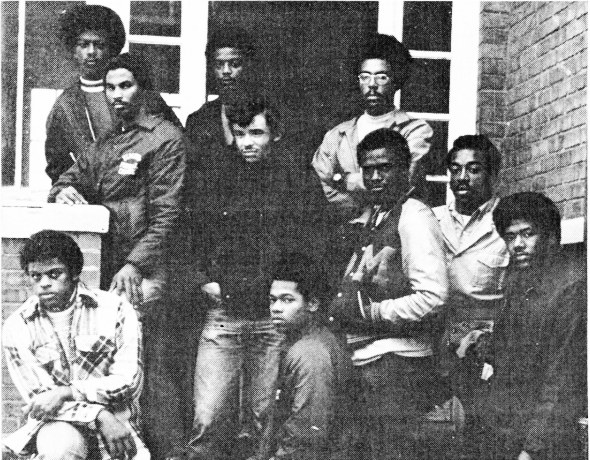

While Elmhurst College archives and newspapers referred to the 11 African American football players involved in the 1970 strike as “blacks,” the December 3, 1970 issue of Jet magazine, a publication geared towards African Americans printed the names of the students. Pictured here are 10 of the 11 football players (top l-r) Michael Redding, Clarence Brister. Michael McCargo,; (second row, l-r) John Spooner, Louis Materre, Paul Thornton, Ed Jones, Steve Brown; (front row, l-r), Greg Black and Rodney Moore. Photo from Jet magazine

On November 9, 1970, a group of African American students met with football coach Wendell Harris and then president Donald C. Kleckner on the third floor of Hammerschmidt Chapel—a moment that became infamous as “The Chapel Incident.”

The students were meeting because of their strike over claims of discrimination in the Athletic Department.

But soon after rumors that Kleckner and Harris were held hostage by the African Americans during the meeting spread like wildfire with local news coverage and campus lore.

“The Chapel Incident” is an example of the racial tensions experienced at Elmhurst College and how the institution in 1970, the “age of protest” navigated different questions of belonging and inclusion—questions that still exists today for the campus. Below are a summary of events that led up to The Chapel Incident and what happened after.

Being African American at Elmhurst College

When Rosie Phillips Davis was a freshman at Elmhurst College in 1967, she was one of 23 other African American students on campus.

In a Leader interview, Davis—who is now the president of the American Psychological Association, the second black woman to hold that position—explained at the time EC did not have a sorority or fraternity, so a group of white and black girls decided to create the first sorority together.

But, according to her, the idea soon fell apart after the white girls went behind their backs to create a sorority.

“None of us were part of it—the first sorority on campus prevented black women,” she said. “The college was involved since you cannot have an on-campus organization without their involvement.”

One night—April 4, 1968 to be exact—the white and black girls got into a disagreement about the sorority and started arguing.

“My friend just walked in,” recalled Davis, “and said, 'You guys are fighting and Dr. King just got shot’.”

Davis credits this incident as one of the events that formed her identity at EC.

“All of it made me way more militant, the whole atmosphere made me feel like that, the deceit of it all,” she said. “It was very racist—we were young people who wanted a sorority; the school was complicit in that.”

But two years later, as a senior and the coordinator of the student group Black Leadership Organized and Consolidated (BLOC), Davis would play a role in creating change on the campus.

How it all started: the football strike

It was October of 1970 when 11 African American football players first voiced concerns of discrimination to head coach Harris. According to a December 3, 1970 issue of Jet magazine, a Chicago publication geared towards African Americans, the players said they were ridiculed with jokes, forced to play while injured, received less playing time, and were severely disciplined in contrast to their white teammates.

Archives reveal that after discussing their complaints with Harris, the 11 players went on strike October 26 until the coach addressed their concerns.

“The first concern of a coach should be the total well-being of his players as individual human beings,” said a notice of the strike sent to Harris and Kleckner signed by all 11 players. “When he refuses to acknowledge this basic right of his players, then his ability as a coach should be questioned.”

But two days later, Harris removed the players from the team, citing missed practices as his reason, Jet magazine reported. Throughout this time, documents show that there were meetings between the players and Kleckner, Harris and athletic director, Walter Schousen, in attempt to solve the situation.

First set of demands

On October 28, the football players meet with Kleckner to present a list of seven demands. These demands included: the hiring of an African American football coach and co-athletic director and fair treatment for all African American players.

Documents also show that the players sent Schousen a memo that described specific charges and incidents of discrimination against their football coaches. The coaches in turn denied the charges in an October 30 response.

“The coaching staff has consistently avoided the use of terms which might be racially offensive,” they said in response to the charge regarding jokes against the black players.

Rally during football game

During halftime of the next football game held October 31, the African American players held a rally to share their concerns and gain support for their cause from the student body. John Spooner, one of the 11 football players involved in the strike, said to Jet magazine that “about 15 whites left the stands to jeers from other whites in the stands.” Spooner also estimated, “about 100 blacks also left the stands to demonstrate their support.”

Athletic Committee investigation

Meanwhile, the allegations of the football players, which Kleckner deemed “very serious” were sent to the Elmhurst College Athletic Committee for investigation.

While it was not meant for the public, the Committee’s report was leaked to The Elmhurst Press, the local newspaper at the time.

“It was our feeling that the specific allegations made by the eleven striking black football players against Coach Harris and his staff were not substantiated by the evidence reviewed by the Committee,” said the report which appeared in the November 18 issue of the Elmhurst Press.

After addressing each allegation, the report ended by saying, “The problems arise not from the specific allegations, but rather from an attempt to express an intangible feeling of dissatisfaction stemming from a lack of understanding.”

In her senior thesis titled “Elmhurst College during the Civil Rights Movement: A Place of Acceptance, Equality and Hope?,” Gina Kachlic ‘11 interviewed Walter Burdick Jr., professor and Committee member, about the backlash the statement received from the public.

“The irony of this incident as the statement was not accusatory, but included only what the Committee discovered through its investigation,” described Burdick in his interview.

The Chapel Incident and second set of demands

The football players along with BLOC members met to discuss their second set of demands on November 9 with Kleckner and Harris in Kleckner’s office on the third floor of the Chapel.

The Chapel Incident occurred in what is now Room 224 of Hammerschmidt Chapel, home to offices of Ron Wiginton, The Leader’s faculty adviser and Bridget O’Rourke, English professor. Photo by Josie Zabran

These nine demands included an “immediate resolution of the football situation,” the hiring of a black presidential aide, as well as a part-time counselor, transparency of financial aid given to black students, active recruitment of black students, and the Afro-American Studies Program be in “complete control” of all operations and subject matter within its department.

“Being on a campus that is the heart of a white suburban area, we are daily attacked by the standards and values that keep us in constant conflict with ourselves and our roles as black people,” said the group’s memo of demands to administration.

But the meeting was unexpected for both parties.

On November 11, 1970, readers picked up the latest issue of the Elmhurst Press with the bold headline “BLACKS ‘HOLD’ KLECKNER, HARRIS” across the front page. The article reported that Kleckner and Harris were “detained [in the November 9 meeting] by more than 100 black students in room 24 of the chapel for 6 1/2 hours.”

In an interview with Kachlic, Bob Clark, who was dean of students during The Chapel Incident, explained he was called to come to campus from his home in Elm Park by Schousen because “black students were holding Dr. Kleckner hostage in the upper level of the Chapel.”

Clark explained that he called the head of campus security at the time “to see if he could get up to Kleckner and see what needed to be done.”

But as it turned out, claims of hostage or kidnapping by the African American students were greatly exaggerated and sensationalized, especially by local newspapers who used it to blame the African Americans.

Kleckner even disproved these rumors in a public speech in a meeting called by Joint Council and the Campus Life Council.

“I did not consider myself kidnapped, held hostage, or detained against my will,” he said while insisting it was he, not the students, who arranged the meeting.

“I said to Lt. Louis Hlavenka of the Elmhurst Police Department, who came into the room, “There is no problem. Don’t worry.””

Davis, who was there at the meeting as a BLOC leader, said the meeting was “confrontational,” but also denied a hostage situation.

“Most black students on campus came, the 100-150 of us who were at Elmhurst College,” she said. “We insisted they [Harris and Kleckner] stay and listen to what we had to say.”

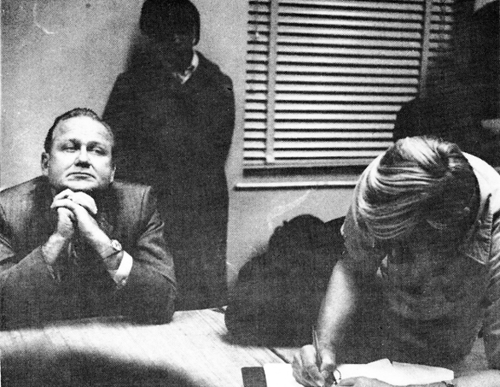

African American students look on as football coach Wendell Harris signs demands while President Donald Kleckner is apprehensive during The Chapel Incident meeting. Photo from Jet magazine.

However, while Harris agreed to most of the demands during the Chapel Incident meeting as well as to reinstate the football players, Kleckner declined to sign the demands.

Community reactions and climate

The Elmhurst Community had varying reactions to the strike, especially after the Chapel Incident.

In a letter to trustees and Kleckner, neighbors of the campus wrote they were “very concerned about the handling of dissident students at Elmhurst College and feel that the coaches are in the clear and the complaints are ridiculous.” The letter further added, that “students should be sent home after all it is our tax money being wasted,” despite the fact that EC is a private institution that did not utilize local tax money.

“The whole attitude here is one of hate,” said Spooner to Jet magazine on the pushback black students were receiving by the town.

Davis is also quoted in the magazine, saying she got a call on her job as a switchboard operator for EC from a man “who said he had 43 policeman and if the school couldn’t solve its n****er problem, they would come and solve it for them.”

Members within EC also had opinions.

While the Elmhurst College Board of Trustees were working on a commission to address the demands of the African American students, trustee chairman EJ Goebel, a relative of EC’s third president, Peter Goebel, provided his personal positions on the “black/white situation” in a December 2 memo.

“Although it is recognized that Elmhurst is a predominantly white suburban area, as are many other areas in which colleges are located, I cannot believe that this hampers the absorbing knowledge and learning offered to alike to all students,” Goebel said in response to the African American students’ second set of demands.

“I cannot help but believe that if any student, black or white feels hampered by our location in the community of Elmhurst that the student should seek a college in another community where the climate might be more healthy for that student’s aims and objectives.”

Resolution

For the next few months, EC dedicated numerous meetings towards the issues brought up by African American students. On March 1, 1971, Kleckner sent the campus parts of the Board of Trustee’s Commission which included reports and recommendations from various departments. The commission agreed black staff should be included in the athletic department as well as the need to communicate “accurate information” about financial aid to students. Trustees also recommended a black counselor be hired and that the financial feasibility of the Afro-American Studies Program to be evaluated.

The board also recommended to establish a procedure for student protests.

“No longer will demands be an accepted form of communication,” said the commission.

While Kleckner signed off on the recommendations, documents are unclear on how much the plans actually panned out.

But Davis noticed changes.

“We saw black faculty hired and black history courses included,” she said.

Parallels today

For many, The Chapel Incident has parallels to recent hate and shooting threat messages that targeted the campus for several weeks and even resulted in cancelled classes as a precaution. The frustration, the anger, the questions of diversity, inclusion and who belongs at EC are conversations and emotions that were had and felt in 1970 as well as today.

Some, like Davis, believe The Chapel Incident sheds light on how to communicate in times of fear and tension—with a president who created monthly bulletins to update the campus on the situation, to student groups like BLOC and the African American football players who led the rally for change through activism, but who were also willing to sit down and discuss.

“How do you handle when people are aggrieved, how do you listen and not fight?” she questioned. “This all could’ve ended differently, we could’ve been arrested, but Kleckner did try to see us as human beings and make a difference.”

Communication is also what Elaine Fetyko Paige, EC’s current archivist, stressed for the future.

“We used to talk, but we’re not anymore,” said Paige. “We need to do more of that.”